- Home

- About Us

- The Team / Contact Us

- Books and Resources

- Privacy Policy

- Nonprofit Employer of Choice Award

Part 1 of this series described what endowments are intended to accomplish, how they work, and why they became relatively common. In this segment, we will find that there can be issues with endowments that lead to unintended consequences.

The issue with basic endowments

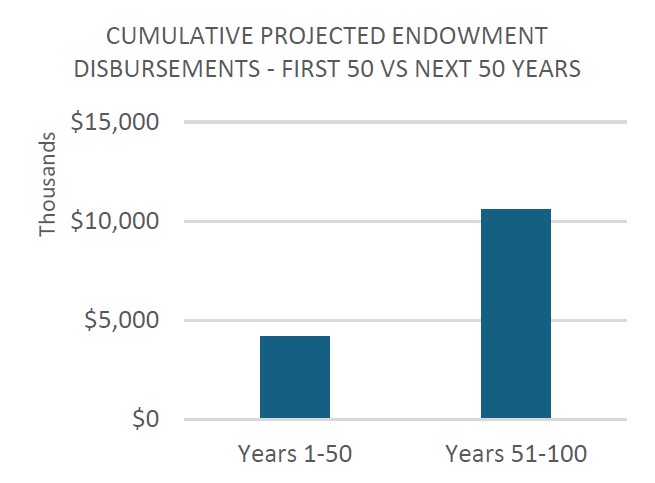

Endowments, over time, can generate a great deal of expendable income to help address charitable purposes, but if a donor’s intent is for timelier impact, a conventional endowment is likely not the right answer. As discussed in Part 1, a $1 million endowment could reasonably be expected to generate over $14 million in income during its first 100 years. Of that amount, only $4 million (28%) would be available for disbursement in the first fifty years of the fund’s life, while over $10 million (72%) is available during the next fifty-year period (Figure 1).

Endowments, over time, can generate a great deal of expendable income to help address charitable purposes, but if a donor’s intent is for timelier impact, a conventional endowment is likely not the right answer. As discussed in Part 1, a $1 million endowment could reasonably be expected to generate over $14 million in income during its first 100 years. Of that amount, only $4 million (28%) would be available for disbursement in the first fifty years of the fund’s life, while over $10 million (72%) is available during the next fifty-year period (Figure 1).

Taken further, the first one hundred years of a conventional endowment is just the start of a never-ending journey. Extending the analysis into future centuries simply worsens the issue, deferring available spending (and impact) indefinitely. Because of their structure, endowments are better able to address future concerns than the concerns of today.

How many donors, if asked, would truly be concerned that their gift still delivers income and impact hundreds or even thousands of years from now? What’s more, it’s difficult to figure out what issues will be among the most pressing far into the future. It is important for donors to consider this to make a well-informed decision about giving.

The risk of deferred impact or irrelevance

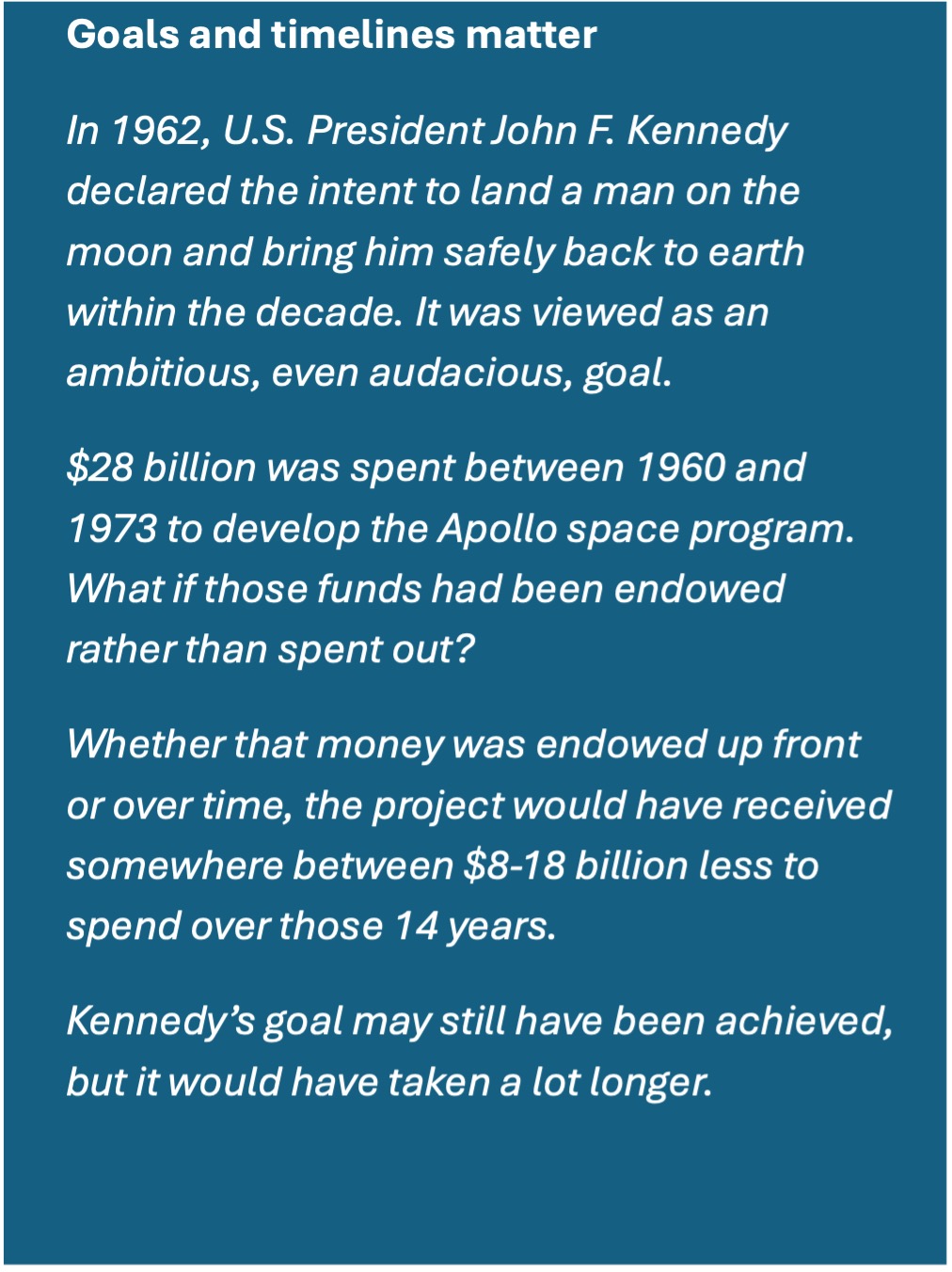

Building on the example provided—assume a donor is interested in addressing inequities that affect historically disadvantaged and marginalized members of society. Establishing an endowment, where significant funding is deferred far into the future will also simply defer impact. If we believe funding can contribute to finding solutions, why not distribute more money over a shorter period (a generation or two) to drive positive change faster?

Building on the example provided—assume a donor is interested in addressing inequities that affect historically disadvantaged and marginalized members of society. Establishing an endowment, where significant funding is deferred far into the future will also simply defer impact. If we believe funding can contribute to finding solutions, why not distribute more money over a shorter period (a generation or two) to drive positive change faster?

Take the example of funding breast cancer research. If a donor believes it is possible that a cure or effective treatment could (or must) be found within 30 years, why not provide funding in a way that increases the likelihood of that goal being achieved?

Another risk with endowments is that their defined purpose may not be relevant in the future. In the example of supporting breast cancer research, if a cure is found for breast cancer within 30 years, will it be possible to repurpose the funds that remain in the endowment? Unless provisions have been made, these funds can be left unspent and “stranded.”

Universities and other charitable organizations have had to seek legal remedies to allow stranded endowment funds to be repurposed. It is unlikely that any donor would be pleased to see their gifts unused or directed to unrelated purposes.

Structuring endowment fund agreements

After due consideration, if setting up an endowment is a donor’s chosen option, gift agreements and endowments can be structured to mitigate the risk.

After due consideration, if setting up an endowment is a donor’s chosen option, gift agreements and endowments can be structured to mitigate the risk.

Many charitable institutions include a “variance clause” or similar terms in agreements like this, for example:

“(Name of charity) may revise or amend the terms of this fund if it becomes difficult to achieve the original purpose of the fund. In making such revisions or amendments, (name of charity) shall consider the general spirit and original intent of the donors.”

This is a useful provision that might allow an institution to redirect funding for breast cancer research to research targeted at other forms of cancer. If the original donor were still alive, they could be consulted, and the agreement could be amended to reflect this change. If, however, the donor is no longer living and has not left more explicit instructions, the decision would be left to the charitable organization. This does not guarantee that the new purpose would be in alignment with the donor’s original intent.

A donor can also consider building specific provisions into a gift agreement at the outset; for example, stipulating the fund be “un-endowed” (wound down) and disbursed either at a specified point in the future or when certain conditions are met (e.g., a cure is found, or the problem solved). Deciding how funds should be disbursed in such cases could be pre-determined and delegated to the charitable organization or family successors, although both options are far from perfect. With every passing generation, the true spirit and intent of a gift can dilute.

Left without such provisions, endowments can go on in perpetuity and, while delivering more money for disbursement each year, push an extraordinary amount of capital into the future, either unspent, or potentially applied to purposes without considering the donor’s original intent.

This is equivalent to the notion of “saving for a rainy day.” Some would argue that it is raining now.

In Part 3: we look at the importance of aligning a donor’s impact horizon (what they want to accomplish over what period) with their gift structure, and how hybrid models, which combine features of both expendable gifts and endowments, can serve the intended purpose.

Peter Fardy is Principal, Northport Philanthropic Advisory Services, and former Vice-President, Advancement, Dalhousie University.